On a bright and breezy April Sunday, we set off for Forest Hill. From north London, this is usually pretty easy as there’s an overground train that runs from Highbury and Islington. On this particular day, though, this part of the station was closed, meaning a far lengthier schlep down to Victoria Station and then onto an overground train that wound a long and circuitous route down to deepest south-east London. Door to door, it took us almost two hours to even get to the start of this walk as a result!

On leaving Forest Hill station, we headed up the A205 – London Road – towards Horniman Museum, walked past the main tower and building and then entered the gardens through the gate on our right. We decided the gardens were a good place to stop and have lunch.

From there, we walked up to the bandstand, where a local food market was in full swing, which led to endless demands for ice cream from the kids, all of which fell on deaf ears! Just past the bandstand are some steps leading downwards and at the bottom of those, we turned right, following the path as it curved round to the left.

From the gardens, we got a great view of the famous Dawson’s Height estate in East Dulwich. Designed by Kate Macintosh and built in between 1964 and 1972, the estate sits on top of a spoil tip from the creation of a nearby railway line.

Dawson’s Heights consists of 298 flats distributed over two blocks and 12 floors, and has a modernist style, reminiscent of a ziggurat. The purpose of this design was to ensure that two thirds of the flats had views in both directions, including towards central London. English Heritage have described the estate as having “a striking and original massing that possesses evocative associations with ancient cities and Italian hill towns.”

As the path curved downwards, we went through a gate on the right into a little path that ran downhill along the perimeter of the park.

At the bottom, we came to a junction of paths, where we turned left and then turned right into the railway embankment nature reserve. Apparently, this is one of the oldest nature reserves in the city, and once constituted part of Crystal Palace and South London Junction Railway on its approach to what was once Lordship Lane Station.

As we near Lordship Lane, the path along the top of the embankment forks both left and right. We turned left to rejoin the path we had been on and then crossed Lordship Lane at the very point where it changes its name to London Road. The change is to do with the fact that this was once the boundary between the Manors – or Lordships – of Dulwich and Friern.

On the corner of the main road and Sydenham Hill sits this lovely old decaying red telephone box. We crossed back over to the right-hand side of the road here.

We then turned left onto a path that leads off between houses, passing this rather spooky-looking place on our right.

We followed the path to the right as it wound winds slowly upwards along a line of lamp posts and through a rather lovely little estate, where the blossom was out.

The path then ran along the perimeter of the woods until we came to a gate into Sydenham Hill Wood on our right.

The existence of this lovely area of woodland is down to a famous 17th.-century actor and theatre proprietor called Edward Alleyn, who bought the Manor of Dulwich for the princely sum of £5000 in 1605. Alleyn was born in 1566, the son of an innkeeper in Bishopsgate, and found fame and fortune in the theatre. He was so famous he even had a sonnet composed in his honour by his friend Ben Jonson.

According to an oft-repeated but sadly discounted tall tale, his life was transformed as a the result of a theatrical apparition. The cast a play in which he was performing contained twelve demons, but one night he found himself somehow confronting thirteen of them and decided that this was a sign he should stop and re-assess his life. He subsequently left the theatre and devoted the rest of his time on earth to good works.

After his move to Dulwich in 1613, he started reshaping the whole area. He founded almshouses for the poor and schools, including the famous Dulwich College. Today, Dulwich Village remains one of the most select and chi-chi London suburbs and much of the area is still under control of his estate.

Alleyn’s original bequest ordered that a portion of his estates should remain a woodland, which was divided into ten equal portions, and which would be lopped in rotation to supply the college with fuel. The names of manor these portions still survive in one form or another: Lapse Wood, Low Cross Wood, Kingswood, Peckarmans Wood . . . and the 27-acre Sydenham Hill Wood here.

The wood now belongs to the London Borough of Southwark and is managed by the London Wildlife Trust. The rest belong to the College Estates and have, until recently, bent kept strictly private.

Once we’d entered the wood through the gate, we turned right, descending the slop to reach a little footbridge. It was, however, closed for repairs.

This forced us down a little slope and along the side of the scaffolding and hoardings. This cutting we pass through was where the railway used to ruin en route to its final destination at the Crystal Palace High Level Station.

In 1871, the impressionist painter sat on this bridge painting a view of the steam train puffing towards him out of Lordship Lane Station, through a landscape that was largely fields. The painting can today be seen in the Courtauld Galleries in the Strand.

Once we reached the upper side of the far bank, we turned left along the main path, passing this sign on our right and slowly heading downwards to the right.

It was whilst walking in these woods that the poet Robert Browning composed his famous lines:

‘The lark’s on the wing, the snails on the thorn

God’s in his heaven – all’s right with the world.’

We continued on the path keeping close to the golf course on our right, and then later to the allotments which succeeded them. At the top of the allotments, the path curved round to the right. We followed the broad track ahead, keeping the chain link fence off to the right.

It was in this thickest, stillest part of the wood that the ‘Dulwich hermit’ Samuel Matthews is said to have made his home. Matthews came from Wales to work as a gardener in Dulwich College, but after the death of his wife in 1796, he retired into seclusion. Here in the woods, he dug himself a cave in the mud and roofed it with fern and brambles, remaining there until his friends heard about his condition and took him back to Wales.

He managed to escape their ministrations and made his way back to his hoke in these woods, where on 23 December 1802, he was found murdered. The rumour had arisen that he was a miser guarding a stash of treasure – who else would anyone want to live in solitude in the wild? Samuel was found with a hook in his throat with which the killers had tried to drag his body from the low-entranced cave.

The case remained unsolved until 1809 when, on his death bed in the Lewisham Workhouse, a man called Isaac Evans confessed to being the perpetrator of the ‘Dulwich Woods tragedy’.

We kept straight ahead, ignoring cross paths.

We passed a few unusual trees along the way.

And eventually came to a clearing where five paths met. We kept straight on over the clearing.

And along another quiet, richly-wooded path . . .

. . . before finally reaching a gate in an iron fence.

Here, we turned left along the tarmac lane, which curved quite steeply uphill.

A rather over-zealous local eco-warrior had decided to adorn the wooden fences shielding the gardens of the lovely 60s modernist houses off to the right with graffiti.

At the top of the tarmac lane, we came to Crescent Wood Lane, opposite the Dulwich Wood House pub.

Most of the construction traffic to the Crystal Palace must have come along Sydenham Hill as, at that time, only Penge Road (now College Road) provided a direct connection to the area from Dulwich and that had a tollgate on it. The first new building on the Estate land was this very pub.

There are records that suggest that it may have been there as early as 1853 – when a man called Augustus Henry Novelli was living on the site. Given the number of workers and the passing traffic all related to building in the vicinity, there would have been a demand for refreshment and food and it may be that a beer house (which did not need then a licence) was set up on the site very early on. The Italianate building was erected as a private house. It has a central square lookout tower with ranges on either side.

The general consensus, though, is that it was constructed between 1857-58 by Francis Fuller and the Crystal Palace Company, and it may have been designed by Charles Barry (Junior). However, the licence was not granted until 25 March 1867.

An interesting feature inside is a wall with pictures and old newspaper cuttings relating to when the nearby Crystal Palace burned down.

Opposite the Dulwich Wood House was this lovely red-brick house, which was originally the gatekeeper’s lodge of Beltwood House, a Grade II listed mansion with fifty rooms and three acres of wooded grounds. According to its Wikipedia page, the building has had a very chequered history, having been everything from a commune to a children’s hospital to the site of endless noisy parties which resulted in the then-owner being forced out for breaches of anti-social behaviour regulations!

Between 1934 and 1936, John Logie Baird, inventor of television, lived few doors along – at 3 Crescent Wood Road. His TV laboratories were situated in the nearby Crystal Palace and were completely destroyed in the fire of 1936.

We would later get a fine view of Baird’s ‘memorial’ – the BBC TV aerial atop the Crystal Palace Hill.

We turned right at the top of the tarmac path and reached the junction with Sydenham Hill, which we crossed. Ever so slightly to the right was Wells Park Road, which is home to this new-build estate.

The high location of Sydenham Hill and its location on what was once the border of Kent and Surrey, with the air said to come straight from Brighton, meant this area became very desirable during the Victorian era. Upper Sydenham came to consist of large, wealthy family villas, whilst the working people lived in Lower Sydenham below.

This place in Wells Park Road had clearly seen better days, though.

After passing Langton Avenue on the right, we enter Sydenham Wells Park through a gate on the right and then bore to the right to walk downhill.

In 1640, the discovery was made on the Sydenham portion of the Westwood Common of wells whose water was of ‘a mild cathartic quality, nearly resembling those of Epsom.’ As their fashionable use developed, they were said to have ‘performed great cures in scrofulous, scorbutic (no, me neither!), paralytic and other stubborn diseases’. One contemporary commentator went so fas as to claim they were ‘a certain cure for every ill to which humanity is heir’.

The wells were covered over in the mid-19th. century, but a scientific analysis of the waters was made many years later during a temporary re-emergence of a spring near Crystal Palace. They were found to contain large quantities of magnesium sulphate – more commonly known as Epsom Salts.

We passed a second entrance gate off to our right, heading straight ahead at the crossing of paths and continuing along the broad tarmac path.

On our left, we passed some ornamental gardens adorned with palm trees.

Sydenham Wells Park now consists of seventeen and a half acres of undulating slopes and was originally purchased by the Metropolitan Board of Works, which laid out the pathways, plantations and succession of small lakes and rivulets.

The main speech at the parks’ opening in 1901 was made by the trade unionist and socialist John Burns, an appropriate choice for a number of reasons. Earlier in his life, Burns had for six months driven the first electric tram in England, one of the ‘features’ in the Crystal Palace Park. He’d also been particularly interested in the right of public meeting in parks and on commons. He was a leader of the Dock Strike in 1889 and then became MP for Battersea, sitting as one of the first Independent Labour Party members in the House.

We came to the first lakes and immediately afterwards, took a sharp right to reach the gate onto Longton Avenue.

We crossed Longton Avenue and went straight up Ormanton Road.

On our left, we passed a couple of these strangely lovely little houses that looked like post-war pre-fabs that had somehow withstood the test of time.

We crossed a street with another name rooted n the area’s old woodlands – Westwood Hill, which was home to some grand abodes.

We turned left and then off to our right entered Charleville Circus, where we came across this marvellous old DAF car. You can follow the Circus either to the left or the right as both directions meet again in a few hundred yards.

We then came to (and crossed) Crystal Palace Park Road, home to some even grander old houses.

Though as you can see from the multiple buzzers here, very few of them are still single-occupant homes and most have been carved up into multiple flats and bedsits.

We turned left down Crystal Palace Park Road and entered Crystal Palace Park through the Fisherman’s Gate on the right. On turning left as we entered, we got the rear view of some of these lovely old houses.

The original Crystal Palace was Prince Albert’s idea. Queen Victoria’s husband dreamt of a Great Exhibition displaying the power and scope of British imperialism, a monument to Victorian self-confidence and its cultural domination of the world. The design of the building, which would itself reflect these achievements, came about almost by accident. A member of the organising committee, while reading a copy of the ‘Illustrated London News’, noticed a picture of the greenhouses at Chatsworth, built for the Duke of Devonshire by Joseph Paxton. Thus, the idea for the Crystal Palace was born.

The Palace was erected by Paxton in Hyde Park in 1851, but its popularity led the organisers to look for a permanent home for the building once the exhibition was over. In 1852, road and rail wagons carried 9,642 tonnes of iron, 300 tonnes of glass, 13 miles of guttering and 200 miles of wooden sash out to the top of Sydenham hill. The 1608-foot-long Palace was re erected on a site the overlooked London, Kent and Surrey.

The extravagant grandeur of the Palace now had to be matched in the layout of its 200 acres of grounds. In a brilliant imaginative stroke, the shimmering glass surfaces of the palace, with their ever-changing play of light, were recreated in the grounds in the shimmering and shifting surfaces of a water park. The whole design of the grounds was to meet this end 11,788 separate jets and fountains, 10 miles of underground piping and a complex system of reservoirs fed from their own artesian well.

On its grandest nights the park could put on a display consuming as much as 6,000,000 gallons of water, with its highest jets reaching 250 feet into the air.

Palace and grounds were opened by Queen Victoria on 10 June 1854 before a crowd of 40,000 people. It became a pleasure garden for the nation, a forerunner of the theme park, with exhibitions, choral festivals, fun fairs, balloon ascents, aeronautical shows, and pneumatic railway, an electric tram ride, spectacular firework displays and a wide range of theatrical and sporting events. Even the FA Cup final was staged here from 1894 to 1924.

At the top of the hill here, you can see the Crystal Palace transmitting station, located on the site of the former television station and transmitter operated by John Logie Baird from 1933. The first transmission from Crystal Palace took place on 28 March 1956, when it succeeded the transmitter at Alexandra Palace, where the BBC had started the world’s first scheduled television service in November 1936.

Here you can see the Crystal Palace Bowl, a natural amphitheatre where large open-air summer concerts were held for nearly 60 years, including Pink Floyd, Elton John, Eric Clapton and the Beach Boys. The stage was rebuilt in 1996 with a permanent structure designed by Ian Ritchie, which was nominated for the RIBA Stirling Prize, but it later fell into a state of disrepair and became inactive as a music venue. In 2020, the London Borough of Bromley Council announced they were working with a local action group to find “creative and community-minded business proposals to reactivate the cherished concert platform” and on the day we passed by, there was a very noisy drum group doing their thing.

As can be seen here, the Bowl also hosted Bob Marley’s largest and last ever concert in London on 7 June 1980.

Victorian architecture, for all its pretensions, is amongst the most exuberant and exciting in the country, but its extravagance was unsustainable by a later age. By the early 20th century, the grand Crystal Palace had become a liability. It must have been a sad and shabby site in its decline, it’s acres of windows cracked and grubby, it’s miles of iron girders rusting, it’s mountains no longer functioning and its grand pubs weeding over. The end was sudden. It came on the night of 30 November 1936, a night my dad, who was six at the time and living in Camberwell, remembered right up until his death.

The fire which destroyed the Crystal Palace was attended by 90 fire engines and could be seen from as far away as Brighton. A sea of molten glass upload down Anerley Hill and the great organ could be heard eerily playing itself as fire-heated draughts of air rushed upwards through the pipes.

By the morning, nothing but two flanking water towers remained. The circumstances surrounding the fire remain a mystery. An official account blames it on a workman’s blowtorch igniting a paint store, but popular accounts take note of the fact that an ‘accidental’ fire had conveniently disposed of a loss-making liability.

All that remains today is the arcade terrace at the top of the park, on which the foundation of the glass edifice once rested, together with a few half ruined sphinxes and statues. They reinforce the melancholy that pervades the site and which the grandeur of the view fails to dissipate. The ghost of what once was, of the last splendour of a more certain age, hangs heavy here.

We meandered through the park, particularly enjoying the area by Lower Lake.

The lake is so divided by bridges, paths and islands that it actually looks like several lakes. It was the main reservoir for the park and its water levels fluctuated so greatly when the water displays were in operation that it became known as the tidal lake. The largest of the islands contained, from 1953, a Children’s Zoo, which will hopefully one day be restored to the site.

The other two islands carry creatures more ancient – the famous prehistoric monsters which form one of the strangest listed buildings in London. From the incongruously mown grass – for a neurotic municipal tidiness intervenes even here – amidst a backdrop of cypresses, juniper, pines and monkey puzzle, they stick their heads up over rocks, grimace in their green and concrete way and fail to frighten the waterfowl, whose only real concern is to get the next hand out of white bread from the Sunday afternoon strollers.

There’s a pterodactyl about to take off, eyes glaring, one paw raised; there are prehistoric crocodiles under the weeping willows, with long and narrow snouts whose bulbous ends look like eye droppers; tortoises with fangs; amphibious dinosaurs with corkscrew necks, and the mighty iguanodon, with skin as rough as a lychee, snarling to keep up appearances . . . whilst obviously wondering what the hell is going on.

The display as a whole was intended to illustrate the course of evolution, working from West to east across the park. It was designed by the delightfully named Waterhouse Hawkins, with scientific advice provided by Professor Richard Owen, the man who gave the world the word ‘dinosaur’.

On New Year’s Eve 1854, when the work was just completed, they gave a dinner party in the open belly of the iguanodon, its top half being cemented in place later.

Eventually, we reached the top left corner of the park, where Crystal Palace overground station sits, and began the long trek home.

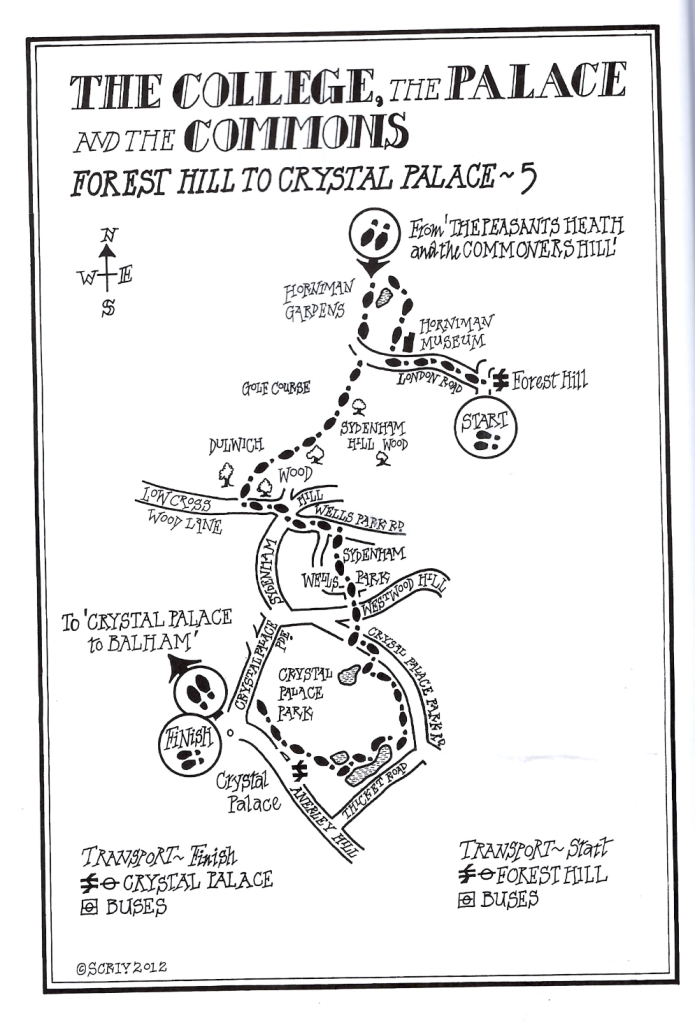

Hopefully, the description and photos above will help anyone wanting to do this wonderful walk, but just inc are, here’s a copy of the map from Bob Gilbert’s book ‘The Green London Way’ too, just in case.